“No physician is really good before he has killed one or two patients.” – Proverb

Software entrepreneur culture is full of stories of the products that succeeded. But what about the products that failed? We rarely hear much about them. This can lead to a very skewed perspective on what works and what doesn’t (survivor bias). But I believe that failure can teach us as much as success. So I asked other software entrepreneurs to share their stories of failure in the hope that we might save others from making the same mistakes. To my surprise I got 12 excellent responses, which I include below along with one of my own. It is a small sample and biased by self selection, but I think it contains a lot of useful insights. It is an unashamedly a long post, as I didn’t want to lose any of these insights by editing it down.

Software entrepreneur culture is full of stories of the products that succeeded. But what about the products that failed? We rarely hear much about them. This can lead to a very skewed perspective on what works and what doesn’t (survivor bias). But I believe that failure can teach us as much as success. So I asked other software entrepreneurs to share their stories of failure in the hope that we might save others from making the same mistakes. To my surprise I got 12 excellent responses, which I include below along with one of my own. It is a small sample and biased by self selection, but I think it contains a lot of useful insights. It is an unashamedly a long post, as I didn’t want to lose any of these insights by editing it down.

Case #1: DRAMA

Contributor

Andy Brice.

The product

DRAMA (Design RAtionale MAnagement) was a commercialization of a University prototype for recording the decision-making process during the design of complex and long-lived artefacts, for example nuclear reactors and chemical plants. By recording it in a structured database this information would still be available long after the original engineers had forgotten it, retired or been run over by buses. This information was believed to be incredibly valuable to later maintainers of the system, engineers creating similar designs and industry regulators. The development was part funded by 4 big process engineering companies.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

Everyone told us what a great idea it was, but no-one bought it. despite some early funding from some big process engineering companies, none of them put it into use properly and we never sold any licences to anyone else.

What went wrong

- Lack of support from the people who would actually have to use it. There are lots of social factors that work against engineers wanting to record their design rationale, including:

- The person taking the time to record the rationale probably isn’t the person getting the benefit from it.

- Extra work for people who are already under a lot of time pressure.

- It might make it easier for others to question decisions and hold companies and engineers accountable for mistakes.

- Engineers may see giving away this knowledge as undermining their job security.

- Problems integrating with the other software tools that engineers spend most of their time in (e.g. CAD packages). This would probably be easier with modern web-based technology.

- It is difficult to capture the subtleties of the design process in a structured form.

- A bad hire. If you hire the wrong person, you should face up to it and get rid of them. Rather than keep moving them around in a vain attempt to find something they are good at.

- We took a phased approach, starting with a single-user proof of concept and then creating a client-server version. In hindsight it should have been obvious that not enough people were actively using the single-user system and we should have killed it then.

Time/money invested

At least 3 man years of work went into this product, with me doing most of it. Thankfully I was a salaried employee. But the lack of success of this product contributed to the demise of the part of the company I was in.

Current product status

The product is long dead.

Any regrets?

It was a fairly painful experience. I would rather have spent all that money, time and energy on something that someone actually used. But at least I learnt some expensive lessons without using my own money.

Lessons learned

- Creating a new market is difficult and risky.

- Changing people’s working habits is hard.

- Social factors can make or break a product. The end-users didn’t see anything in it for them.

- If the end-users don’t like a product, they will find a way not to use it, even if their bosses appear to be enthusiastic about it.

- Talk is cheap. Lots of people telling you how great your product is doesn’t mean much. You only really find out if your product is commercially viable when you start asking people to buy it.

Case #2: CleanChief

Contributor

Sam Howley.

The product

CleanChief was to be ‘The easy management solution for cleaning organisations’. Managing assets, employee schedules, ordering supplies, you name it CleanChief handled it. Essentially it was light weight accounting software for cleaning companies.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

A small number of copies were sold. No one is actively using it at present. Once I realised that it wasn’t a complete product and that additional development was required I moved on to other product ideas. I had basically run out of enthusiasm for the product.

What went wrong

- I am not an accountant.

- I have never run a cleaning company.

- I developed it for more than two years without getting feedback from real cleaning companies. I was arrogant enough to think that I knew what they wanted (or could work it out on my own). Or maybe it was that I was just where I was most happy and comfortable – writing software. Talking to real users was new and to be honest a bit scary for me.

- A successful cleaning company operator, a friend of a friend, offered to become involved for a 30% share. This was a gift from the heavens, exactly what I needed. I refused.

- In a way, even though I spent so long on the product, I gave in too soon, I was just getting feedback from real users, just getting my first batch of sales when I decided to move on.

- I developed the application in VB6 even though I knew it was outdated technology when I started the project.This meant there was no ‘cool factor’ when discussing it with other developers, I told myself it didn’t bother me, but it probably did.

Time/money invested

I worked on it at night and weekends for about 2 1/2 years. I paid for graphic design work, purchased stock icons and images. I probably spent a couple of thousand Australian dollars in total and an awful lot of time.

Current product status

I moved on to other products that have gone much better. My newer products were released in months rather than years and I looked for real feedback from real users from day one. they are:

I do occasionally ponder returning to CleanChief and trying to raise it from the ashes.

Any regrets?

No. Looking back I learned a few lessons from a huge amount of time and work, it was a very inefficient way to learn those lessons. But when you are new to something like starting a business or creating useful software being inefficient at learning lessons is the best you can do, it’s a thousand times better than not learning lessons at all.

I learned so much more in my two and a half years of trying to develop CleanChief than I did in the two and a half years prior to that, during which time I really wanted to start a software business but didn’t take any action.

Lessons learned

Hearing or reading some piece of advice is totally different to living it. Here are some of the ideas that I always agreed were true but didn’t fully understand the implications of until I had lived them out:

- Force yourself to get out and talk to people. Ask their advice. Almost everyone will help if you ask them for feedback.

- Force yourself to cold call a few businesses in your target market.

- Create a plan of how to market your product.

- Try and use your product as much as possible as you build it.

- Get out of your comfort zone from day one

- Do not have the mind set that the day you release version 1.0 is the finish line, it’s the starting line, so hurry up and get there.

Case #3: Chimsoft

Contributor

Phil Anderson.

The product

ChimSoft – Software for Chimney Sweeps.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

I believe this failed for two reasons:

- Focusing on too small of a niche

- Me not being able to work full time on it.

I don’t consider it a complete failure because I sold two copies when it retailed for $2k, and maybe 10-15 more copies when I lowered the price to $200. Those sales proved that I wasn’t completely off base in thinking there was a market for the software, but the cost of customer acquisition and the size of the market were too small. Customers wanted to have a bunch of phone calls, face-to-face etc… the type of stuff you only see with much more expensive software. The problem was that for a niche this small we had to charge a lot of money to make it worthwhile for us, but the customers were small businesses where this is a major investment, so the fit was never right. The other issue was the people that did buy it were not super tech savvy, so there was a high cost of support that made even a $200 product not worth it.

What went wrong

- Having all partners who were not full-time, and had equal equity. I ended up doing most of the work and this is the main reason I didn’t force success is I felt I was in it alone.

- Focusing on too narrow of a niche. The plan all along was to expand for all service industries, but it was much harder to make that move than we expected.

- Not researching pricing more, we knew small businesses made major purchases for things that really helped their business, but I think it would have been better to have a cheaper product with wider appeal than an expensive product with narrow appeal.

Time/money invested

I invested maybe a year of time and $3k into the company. I did not take any huge risks on it, so there were no big negative outcomes.

Current product status

The company folded in 2007, I refocused my efforts on my existing companies (AUsedCar.com and BudgetSimple.com) and both have been doing well enough that I quit my day job.

Any regrets?

I don’t regret it entirely, I think I learned several valuable lessons about working with other people, small business sales, trade-shows and software development.

Lessons learned

- Pick partners wisely. Don’t try to be even-steven with equity. Use restricted stock to ensure everyone does their part.

- Know what your customers expect (24/7 phone support?) to determine if you can do this while working a day job.

Case #4: PC Desktop Cleaner

Contributor

Javier Rojas Goñi.

The product

PC Desktop Cleaner. Simple software that cleans your desktop and archives your files.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

My goal was to sell 10 units per month. I’ve sold less than 1 unit per month.

What went wrong

- I think that the product concept is not useful enough. It’s not a thing that people would pay for.

- The market exists (some people buy) but it’s too little or difficult to reach.

- I didn’t do any market research. I just got in love with the idea and did it. Later, I’ve learnt to use “lazy instantiation marketing” and have trashed a lot of embryo projects. :-)

Time/money invested

I think I wasted near $500 in development tools and some freelancers. Not too much.

Current product status

I’m still selling it. I’ve thought about others products, but not really decided yet.

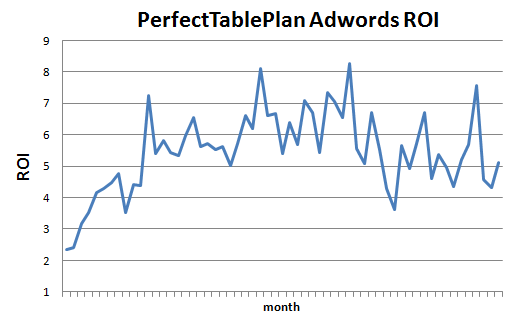

Any regrets?

No, it was a lot of fun and I learnt lot of things. In my “day job” I own a small firm that sells software for production scheduling. I’ve learn a lot of SEO and AdWords in the DesktopCleaner project that now I’m using with great results.

Lessons learned

Go for it, maybe you win, maybe you fail, but you will grow and get tons of useful knowledge on the way.

Case #5: Smart Diary Suite

Contributor

Dennis Volodomanov.

The product

Smart Diary Suite.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

It sells and the profits cover current investments in the product, but there is little left over on top of that.

What went wrong

If I had a chance to do anything differently:

- Take it seriously from day one.

- Never stop developing and supporting.

- Invest as much as possible in marketing early on.

- Don’t stop believing in your creation.

Time/money invested

Up to this point, I have spent 13 years on Smart Diary Suite and a lot of money went into buying hardware, software, hosting, marketing, etc… All of that money came from my day job, but at this point SDS has recovered all of that back and is now making a small profit. The actual amount is hard to calculate (over the 13 year span), but we would be talking in tens of thousands of US dollars.

Current product status

For a while it may have seemed like SDS is not going to be successful, but that’s probably my fault – I stopped believing for a little while. Now I am back, starting again and this time I’ll make sure it doesn’t fail.

Any regrets?

I do not regret doing it. I regret allowing myself to stop working on it, basically bailing out on it for a while – that is my biggest mistake.

Lessons learned

If you want a successful product – believe in it and let others know that you believe in it.

Case #6: Highlighter

Contributor

Mike Sutton.

The product

Highlighter. A utility to print neatly formatted, syntax highlighted source code listings.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

I earnt a grand total of £442.52 (about $700 in todays money) in just over two years, so I guess it paid for itself if you exclude my time.

What went wrong

Since it was my first product and I was very green about both marketing and product development. I would suggest the following would have made things better:

- Get feedback from potential users about the product (eg from the ASP forums). Some parts of the program where probably too option heavy and geeky.

- Diversify. If people didn’t want to print fancy listings, maybe they would have wanted them formatted in HTML.

- Better marketing. I’m not sure this would have saved it, but all I knew in those days was uploading to shareware sites. I never even sent a press release.

I figure it failed simply because it was a product nobody wanted. Actually, more importantly than that,, it was a product *I* didn’t want to use, but it developed from a larger product I was working on, on the assumption I could earn some money on the side from part of the code. Since then I’ve stuck to products which I’ve actually wanted to use myself. There’s a lot to be said for dogfooding, not just for debugging, but for knowing where the pain points are and what extra features could be added.

Time/money invested

I would guess a couple of months of evening/weekend development time. Financially there was little spent, except that I offered the option of a printed manual and CD for an extra charge. One customer took me up on the offer, so I had to get 100 manuals printed and 99 of them went in the bin.

Current product status

I moved on to another product which has sold over £50,000 and a third which has earnt even more than that. Not enough to retire on but considering I only do this part time it must work out at a great hourly rate. There’s a lot to be said for not giving up…

Any regrets?

Nope. I figure every failure in life teaches you valuable lessons. Of course if I’d made a large financial investment I may feel differently, but that’s one of the big advantages of software over physical product sales.

Lessons learned

Just to reiterate – develop something which you find useful, instead of second guessing others.

Case #7: R10Clean

Contributor

Steve Cholerton.

The product

R10Clean. A data cleaning and manipulation tool.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

In the 18 months or so it’s been on the market I have sold 6. It has been £199, £99 and £19 – with no effect on sales !

What went wrong

Not sure what I did wrong ? The product is maybe too techie ?

Time/money invested

No effect financially as at the time I was in a strong financial position.

Current product status

I still have it for sale but do not market it at all. I have other products.

Any regrets?

I don’t regret it as it saved me a ton of time when I was working with legacy databases a lot, as a commercial product it has been raved about (once!) and received a good review from the Kleper report, but has failed totally.

Lessons learned

Advice to others ? Just because you need it personally, don’t assume the rest of the world does too. :-)

Case #8: nBinder

Contributor

Boghiu Andrei.

The product

nBinder, packs multiple files into a stand alone executable with over 50 advanced output and file unpack options, conditional run and commands.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

It was the first product I began selling. It sold to 300+ customers in 4 years. But for about a year the sales began to go down and have finally stopped completely.

What went wrong

- The biggest problem was that because it was a packer intended for people that wanted to pack their products (software or games) into a single package (compressed and encrypted) many have used it for creating malware by binding malware files to legit files and then distributing the output so it isn’t detected by antivrus software (although it would be detected at runtime). Because of this I had lots of problems with antivirus companies that flagged files create with nBinder as malware. This was of course affecting legit users as their files would be falsely marked as malware. I used virustotal.com to see which antivirus detected it and contacted the antivirus manufacturer as soon as I detected the problem. In most cases they would remove it from their definitions. But it was an uphill battle because it would appear again in a matter of weeks. Some small AV companies didn’t event bother to reply to my emails to fix the problem. Others were using heuristics to flag files create with my applications and AV developers were reluctant to whitelist files created with nBinder. You can imagine it that it was enough for an AV such as Kaspersky or Norton to pick my files as malware for a day and customers would be affected and not use my product any more, especially that it took about 3 days for AVs to remove the false positive.

- Infrequent updates. Due to lack of time I only updated the product once or twice a year and this affected the product a lot.

- No marketing. I decided that I didn’t want to invest money in marketing so, except for a short AdWords campaign, I invested no money in marketing.

- My decision to develop 3 products instead of concentrating on one or two affected development time and quality. I have worked on 3 products simultaneously instead of concentrating on making a single good one. The reason I worked on 3 is because I enjoyed developing different software in different categories. I didn’t start this for money but for the fun of development.

Time/money invested

I invested almost no money (except for hosting costs). Time invested I can’t really say exactly, but not too much as I only worked on nBinder in short bursts like 6 hours a day for a week or so before releases.

Current product status

Still for sale. My other products are:

Any regrets?

It’s not a total failure as I did make some money out of it with no investment, so I don’t regret starting it, but it could have been much better.

Lessons learned

Words of advice for others trying to make money from software development:

- Study the market and the current trends very well.

- Before deciding to take on large competition make sure you have something better (at least from one point of view) than the competition ( for example you might not have the same features but you have a better GUI and general presentation).

- Do not get scared of an overly populated market segment. For example with nBinder I picked a segment with very little competition but also few possible users and the results were not so great (I didn’t have many users). With nCleaner I went head-to-head with lots of already established products but also the market is very big. Although nCleaner is free it has had the most success because there are so many potential users (anyone with a PC actually), so it had over 2 millions downloads and I still receive lots of mails regarding it, even if the last update was in 2007. So it is possible to have success in a market with lots of competition with no investment but it’s hard to reach the level of more established products.

Case #9: Net-Herald

Contributor

Torsten Uhlmann.

The product

Net-Herald – a monitoring application for water supply companies. It was a complex client server application that would receive monitoring data from specialized hardware and store that data inside a SQL database. The client displays that data in different graphs, provides printable reports or sends alarm messages via SMS if a monitored value is not within its specified limits.

I developed Net-Herald as a perfect fit for that specialized hardware that is provided by a local manufacturer. That way, so I hoped, I could profit from their sales leads and would find a smoother way into these water supply companies. The downside of course, was that my software would only work with their hardware.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

I sold a first license fairly soon after I had a sellable product, although it took the customer nearly a year until they finally bought. But since then I sold only one more license within the last 4 years or so.

What went wrong

- I didn’t do my own marketing and the hardware guys weren’t really concerned with selling my software.

- Water management companies have a terribly long sales cycle. Other vendors monitoring applications usually cost tens of thousands and are geared toward large suppliers. Whenever a supplier buys into such a product he is unlikely to change within the next decade or more. I tried to position my software towards small suppliers but even then most of them were already locked into another vendor’s solution.

- My software only worked with a specific hardware. That narrowed the marked down substantially.

- In the end the software became too complex for one poor mortal to maintain. Because the software didn’t produce any substantial income I had to stop adding new features which would make it attractive for more prospective clients.

- This kind of software is not sold over the Internet. Rather it needs very active sales people that nurture clients over a rather long period of time.

- All these facts indicate that software like this should not be developed by a one man show.

Time/money invested

The development time for the first sellable version was maybe about 9 months. I didn’t have a job income at that time, but got funding due to government support for small start-up businesses. So I didn’t drain our family’s personal finances. But I did of course invest a great deal of time and sweat.

Current product status

Now, I have drawn a line and stopped active development of Net-Herald. I still do some custom extensions for my first clients. But I no longer market the software. I have instead focused on my consulting services. I also try to learn developing and selling software with my cross-platform drag and drop product Simidude.

Any regrets?

I didn’t succeed yet selling my own software (which is still my goal) but I do not regret doing it. I developed Net-Herald using (Java) technologies that now give me leverage at my consulting gigs. All in all it was a heavy ride. But it was fun and I would do it again.

Lessons learned

- My biggest mistake was the lack of market analysis. I trusted the word of the hardware manufacturer without verification.

- I have written more about the above and some other failures on my blog.

Case #10: HabitShaper

Contributor

Adriano Ferrari.

The product

HabitShaper – set and track daily targets for your goals (weight loss, quit smoking, jogging, writing, etc…).

Why it was judged a commercial failure

I sold a few copies, but not enough to make back the time I invested in it and my conversion numbers and traffic are below average.

What went wrong

- Did not do enough pre-production research (talking to customers, etc).

- Did not do a large enough beta to make up for lack of initial research.

- Ignored gut-feeling that my product is better suited to being web-based and multi-platform (incl. mobile).

- Did EVERYTHING myself (logo, web design, video, software, AdWords, etc).

Time/money invested

I worked on it two years, part-time, while doing Masters/PhD in Physics. It had no impact on my finances (very little money invested) or circumstances.

Current product status

I am relaunching as a web-based product this summer.

Any regrets?

Not in the least! I learned about as much from making HabitShaper as I have from my MSc thesis and PhD work.

Lessons learned

- Most important: PAPER prototypes, minimum viable product, and iterate.

- Don’t be afraid to launch early.

- Launch a little bigger than you’d expect (it’s harder to find those initial customers than you think).

- Don’t be afraid to change directions, especially early on.

- Doing things yourself is a great learning experience, but if you want to get your product out to customers as fast as possible, don’t be afraid to invest money and outsource your weaknesses.

Case #11: BPL

Contributor

Jim Lawless.

The product

BPL – Batch Programming Language Interpreter.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

I sold about 10 copies.

What went wrong

- I didn’t really do enough research to find out if the target market was in existence. I was hoping that network admins and support staff members would find it easier to use than batch files and less complicated than any of the free scripting language options available. So, I just rushed to get the MVP (Minimum Viable Product) out the door.

- I never did provide a compiler that would build a stand-alone EXE. I think that might have met with more success.

- I didn’t do much as far as advertising the existence of the product.

Time/money invested

I only spent a few weeks coding and documenting it in my spare time. Support issues sometimes took a whole evening, but nothing major. It did not have any impact on my finances as I had invested nothing but my time.

Current product status

I will still address support issues with this product for registered users, but I don’t actively sell it. I’ve open-sourced the program and it still really isn’t seeing heavy use.

I was more successful with other products. I have a few retired products that saw some good bulk-purchase deals ( command-line DUN HangUp, command-line scheduler ) and I still sell the following (for Windows):

All of the above still bring in a modest passive income.

Any regrets?

Not at all. “Nothing ventured,…”.

Lessons learned

Had I not attempted to bring the BPL product to life, I might still be sitting here wondering “what if?” I think it was very beneficial for me to invest the time to try out this idea.

Case #12: Anonymous

Contributor

Anonymous.

The product

A time tracker.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

Because it is not my primary income. I have about 150 customers in one year.

What went wrong

- No marketing.

- No real thought into features.

- I don’t spend any time on it.

In my defense, the reason I do not spend much time on it is that the market became saturated with ‘me toos’ right after I released, which was quite expected. In fact, as I was looking for users, I got an email from a competitor suggesting that I don’t enter the market because they are working on the same thing! I don’t know what I would do differently. Maybe spend more time on it? I think the law of diminishing returns applies quite early in this space so I am not sure.

Time/money invested

Since inception (Nov 2008), I’ve spent close to 250 hours total. Total cash outlay was something like $500.

Current product status

I never tried to make it succeed, to be honest. It was only a learning experience for me. What I probably need now is to go all in. Quite frankly, if I double the sales for this product, I can quit all consulting work. But I really do not think it is a good idea to work on this app full time as it is too simple.

Any regrets?

Definitely not.

Lessons learned

- Do it!

- Solve a problem people know they have.

- Don’t invest too much time and money at the beginning.

- Don’t be wedded to a particular idea.

- Don’t only listen to your customers. Listen to yourself. After all, you created the idea which attracted the customers.

- Never promise a feature for a sale. I’ve never done it but the pressure is really great. My stock response is always: “While such a feature may be available in the future, I recommend that you only use current features when deciding on your purchase.”

- Do use Google to your advantage.

Case #13: ScreenRest

Contributor

Derek Pollard.

The product

ScreenRest – a consumer software product that reminds users to take regular rest breaks while using their computer.

Why it was judged a commercial failure

ScreenRest failed commercially because we built a product without having a clearly defined market. This was compounded by it offering prevention, not a solution. ScreenRest continues to regularly sell a small number of licences but not in sufficient quantity to justify further enhancements. The conversion rates are good, but there are simply not enough visitors to the website.

What went wrong

- Not doing market research first.

- Creating a prevention rather than solution product – people generally wait until they have a problem and then look for a solution.

- Creating a product with medical associations – the SEO and PPC competition for related keywords is prohibitive for a product with a low purchase price.

Time/money invested

At least £2000 was spent on the project, including software licences and additional hardware. The product and website were created over roughly 12 months by myself and my wife Lindsay, some during spare time, then part-time and finally full-time so it is difficult to determine the total number of hours. Working part-time and then full-time on ScreenRest caused a significant impact on our finances. Although right from the beginning we saw this as in investment for building a business.

Current product status

Once the product was complete and we started learning SEO it became all too apparent that organic search traffic for related keywords was going to be insufficient. Research into PPC then revealed that the price point was too low to support purchasing medical terms. Planned features for ScreenRest have been put on hold and no further marketing is planned. We continue to support new and existing ScreenRest customers and plan to do so for the foreseeable future. Rather than create another software product we chose to use what we had learned about marketing, copywriting and SEO to create a series of websites targeting a range of topics (often known as niche sites). The most successful of these sites we are expanding in value and functionality to fill gaps not serviced by the competition.

Any regrets?

No. ScreenRest succeeded in every way intended, other than commercially. Creating it was a rewarding learning exercise that started us down a path to finding the intersection of our skills, experience and market opportunities.

Lessons learned

- Start with market research – creating a high-quality product you believe in is not enough on its own.

- Make sure you can identify a specific target market, that you can reach that market and that it is large enough to support your financial goals.

Conclusion

Analysing the above (admittedly small and self-selected sample) it is clear that by far the commonest cause of failure were:

- lack of market research

- lack of marketing

With the benefitof 20/20 hindsight it seems blindingly obvious that we should:

- spend a few days researching if a product is commercially viable before we spend months or years creating it

- put considerable effort into letting people know about the products we create

Yet, by my count, a whopping 6 out of 13 of us admitted to failing to do each of these adequately. Probably we were too busy obsessing over the features and technical issues so beloved of developers, which actually contributed to far fewer failures.

It is also noticeable that, despite the failure of these products, there are few regrets. Important lessons were learned and no-one lost their house. Many of us have gone on to develop successful products and the others will be in a much stronger position if they do decide to try again.

A big thank you to everyone who ate a large slice of humble pie and submitted the above. I hope we can prevent other budding software entrepreneurs making the same mistakes. Even if you don’t succeed, you will learn a lot.

Feel free to add your own hard-won lessons from failure in the comments below.

“No physician is really good before he has killed one or two patients.” – Hindu proverb

Social factors can make or break a product.

Software entrepreneur culture is full of stories of the products that succeeded. But what about the products that failed? We rarely hear much about them. This can lead to a very skewed perspective on what works and what doesn’t (

Software entrepreneur culture is full of stories of the products that succeeded. But what about the products that failed? We rarely hear much about them. This can lead to a very skewed perspective on what works and what doesn’t (

A while back I exchanged a few ideas with Dennis Gurock about names for their new testing product. Choosing a name is difficult, but it is something every product developer has to do. So I asked Dennis to write a guest post about the process they went through before they ended up with ‘TestRail’.

A while back I exchanged a few ideas with Dennis Gurock about names for their new testing product. Choosing a name is difficult, but it is something every product developer has to do. So I asked Dennis to write a guest post about the process they went through before they ended up with ‘TestRail’.

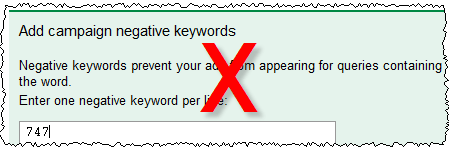

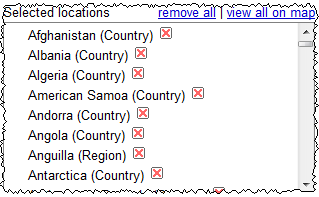

I have looked at quite a few Google Adwords accounts as part of a

I have looked at quite a few Google Adwords accounts as part of a

A few weeks ago I was going to buy a digitizer tablet for my PC. Then I noticed in the vendor’s terms and conditions that they wouldn’t accept a return once I had opened the packaging. But I couldn’t know if the tablet works until I open the packaging. Duh. I didn’t buy it. Similarly I look for a sensible money-back guarantee whenever I buy software. I don’t remember ever invoking such a guarantee for software, but it is nice to know that I could if I wanted to. Also, I see the lack of such a guarantee as a warning signal that the vendor isn’t confident about the quality of their product.

A few weeks ago I was going to buy a digitizer tablet for my PC. Then I noticed in the vendor’s terms and conditions that they wouldn’t accept a return once I had opened the packaging. But I couldn’t know if the tablet works until I open the packaging. Duh. I didn’t buy it. Similarly I look for a sensible money-back guarantee whenever I buy software. I don’t remember ever invoking such a guarantee for software, but it is nice to know that I could if I wanted to. Also, I see the lack of such a guarantee as a warning signal that the vendor isn’t confident about the quality of their product.