TrialPay is an interesting idea. In basic terms:

TrialPay is an interesting idea. In basic terms:

- merchants (e.g. microISVs like me) want to sell products, such as software

- customers want to get a product without paying for it

- advertisers (such as Netflix and Gap) want to sell their goods

TrialPay brings the 3 together by letting the customer get the merchant’s product for ‘free’ by buying something from the advertiser. The advertiser then pays the merchant, with TrialPay taking a cut. The merchant gets paid, even though the customer might not have been prepared to pay the price of their product. The customer gets your product ‘free’ by buying something else, which they might have wanted anyway. The advertiser gets a new customer. TrialPay get some commission. Everyone is happy. I decided to give it a try and signed up in October last year.

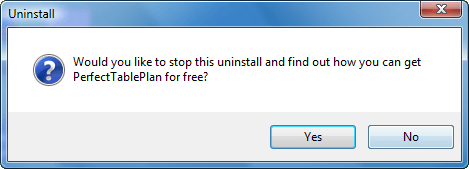

I decided not to mention the TrialPay offer on my main payment page. I could visualise eager potential buyers of my table plan software, credit card in hand, being distracted by the TrialPay ‘Get it free’ logo. Off they would wander to the TrialPay pages and become so engrossed/confused/distracted by the offers there, they would forget all about my product. Sale lost. Instead I modified my Inno setup Windows installer to pop up the following dialog when someone uninstalls the free trial without ever adding a licence key:

If they click ‘No’ the software uninstalls. If they click ‘Yes’ they are taken to the PerfectTablePlan TrialPay page. I hoped that this would entice some of those who had decided not to part with $29.95 to ‘buy’ PerfectTablePlan anyway through TrialPay.

TrialPay allows you to set the mimum payout to any level you like. You can also vary the payout by customer country (e.g. less for poorer countres). The lower the minimum payout you set, the more advertisers deals are available to customers (and presumably the higher the chance of a conversion).

The Minimum Acceptable Payout (or MAP) is the lowest amount you are willing to accept per transaction and determines which advertiser offers are available to your customers. The lower the minimum, the more offers that will appear for your product and the more likely a user is to find an offer that compels him to complete his transaction. While you may set a low MAP, your average payout will greatly exceed the minimums you set. (from the TrialPay website)

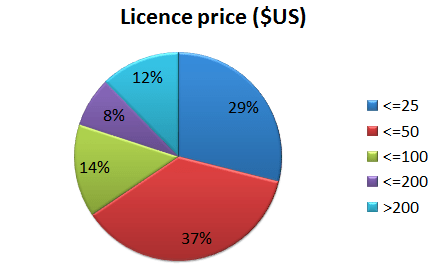

It quickly became apparent that very few advertisers offer deals that pay the $29.95 I charge for my product (possibly none, in some countries).

I set a minimum payout of $25 in rich countries and $20 in poorer ones. After a few weeks with no TrialPay conversion I reduced the mimum payout to $20 in rich countries and $15 in poorer ones. TrialPay suggested that a $2 minimum payout was optimal in Africa and Central America if I was accepting $20 in the USA. $2? I don’t think so. That doesn’t even cover the cost of answering a support email. Especially if they aren’t a native English speaker.

I also gave the TrialPay option a mention in my PerfectTablePlan newsletter. Most of the recipients already have licences, but I hoped that that they might forward it to friends and colleagues.

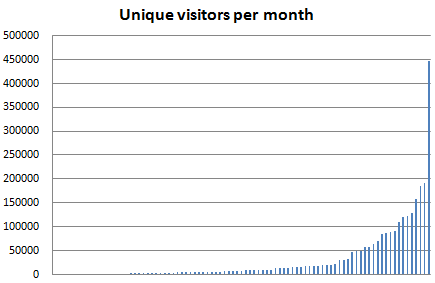

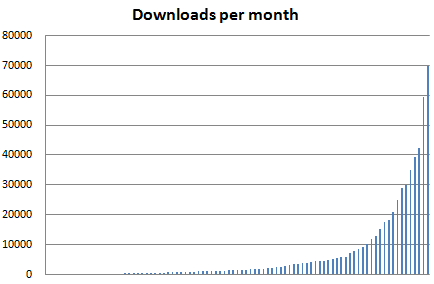

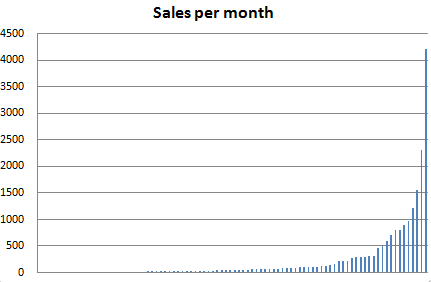

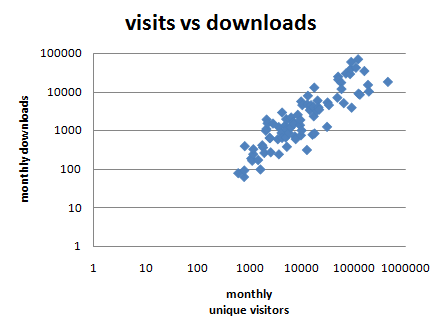

The results to date have not been encouraging. Lots of people have gone to the PerfectTablePlan TrialPay page (approximately 1 for every 10 downloads), but the conversion rate has been dismal. The total number of TrialPay sales since I signed up over 7 months ago is two, for a total of $43.60. That certainly isn’t worth the time it took me to sign up, modify the installer and test the ecommerce integration with e-junkie. I am not sure why the conversion rate was so poor:

- The TrialPay landing page isn’t compelling enough?

- The advertiser offers aren’t attractive enough?

- The concept of TrialPay is too complicated?

- People are suspicious of ‘free’?

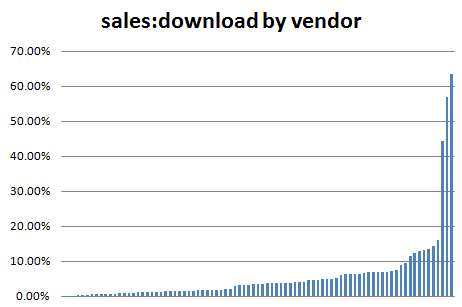

TrialPay’s poster child LavaSoft claim an impressive 5,000 additional sales per month through TrialPay. At $26.95 per licence this is an additional $1.6 million per year. But the numbers look a bit less impressive on closer inspection. 5,000 additional sales/month from 10 million visitors/month is only an extra +0.05% conversion rate[1]. And TrialPay probably didn’t pay out the $26.95 per licence Lavasoft normally charge. It is also noticeable that TrialPay only seems to get a mention on the download page of their free product, not the products they charge for.

Obviously the only way to know for sure whether TrialPay will work for you, is to try it. Your results might be very different from mine. If you do still want to try TrialPay, you can find out some details of how to integrate it here [2].

[1]I am being a little unfair here, as the quoted 10 million visitors probably aren’t just for Lavasoft’s Ad-Aware product.

[2]Note there is a bug in some older versions of Inno setup which means you can’t continue with the uninstall if they click “No” when you display a dialog, as shown above. So, if you are using Inno setup (which I recommend highly), make sure you are using v5.2.3 or later.

I was recently interviewed by Bob Walsh and Patrick Foley for

I was recently interviewed by Bob Walsh and Patrick Foley for

I will be giving a talk entitled “10 mistakes microISVs make” at the

I will be giving a talk entitled “10 mistakes microISVs make” at the  In theory, the Internet allows customers to find products without the need for middlemen (unless you count Google). In reality, the age of full

In theory, the Internet allows customers to find products without the need for middlemen (unless you count Google). In reality, the age of full  It was always on the cards that Google was going to raise the prices of their payment processing service, GoogleCheckout. Up till now I had effectively used GoogleCheckout for free, as they offset their 1.5% + £0.15 processing fee against my Adwords spending. But they are

It was always on the cards that Google was going to raise the prices of their payment processing service, GoogleCheckout. Up till now I had effectively used GoogleCheckout for free, as they offset their 1.5% + £0.15 processing fee against my Adwords spending. But they are