This is a guest post by Joannes Vermorel, founder of the Lokad Forecasting Service.

Software developers seem to be herd animals. They like to stay very close to each other. As a result, the marketplace ends up riddled with hundreds of ToDo lists while other segments are deserted, despite high financial stakes. During my routine browsing of software business forums, I have noticed that the most common answer to Why the heck are you producing yet another ToDo list? is the desperately annoying Because I can’t find a better idea.

Software developers seem to be herd animals. They like to stay very close to each other. As a result, the marketplace ends up riddled with hundreds of ToDo lists while other segments are deserted, despite high financial stakes. During my routine browsing of software business forums, I have noticed that the most common answer to Why the heck are you producing yet another ToDo list? is the desperately annoying Because I can’t find a better idea.

This is desperately annoying because the world is full (saturated even) with problems so painful that people or companies would be very willing to pay to relieve the pain, even if only a little. A tiny fraction of these problems are addressed by the software industry (such as the need for ToDo lists), but most are just lacking any decent solution.

Hence, I detail below 3 low-competition software niches in retail. Indeed, after half a decade of running sales forecasting software company Lokad, I believe, despite the potential survivor bias, that I have acquired insights on a few B2B markets close to my own. Firstly I will address a few inevitable questions:

Q: If you have uncovered such profitable niches, why don’t you take over them yourself?

A: Mostly because running a growing business already takes about 100% of my management bandwidth.

Q: If these niches have little competition, entry barriers must be high?

A: Herding problems aside, I believe not.

Q: Now these niches have been disclosed, they will be swarmed over by competitors, right?

A: Odds are extremely low on that one. The herd instinct is just too strong.

Q. Do I have to pay you if I use one of your ideas?

A. No, I am releasing this into the public domain. I expect no payment if you get rich (unless you want to!) and accept no liability if you fail miserably. Execution is everything. And don’t trust a random stranger on the Internet – do your own market research.

Before digging into the specifics of those niches, here are a couple of signs that I have noticed to be indicators of desperate lack of competition:

- No one bothers about doing even basic SEO.

- No prices on display.

- No one offers self-signup – you have to go through a sales rep.

- Little in the way of online documentation or screenshots are available.

However, lack of competition does not mean lack of competitors. It’s just not the sort of competition that keeps you up at night. Through private one-to-one discussions with clients of those solutions, here is the typical feedback I get:

- Licenses are hideously expensive.

- Setup takes months.

- Upgrade takes months (and is hideously expensive).

- Every single feature feels half-baked.

By way of anecdotal evidence – during a manufacturer integration with our forecasting technology a few months ago at Lokad, we discovered that the client had been charged $2,000 by its primary software provider in order to activate Remote Desktop on the Windows Server where the software was installed. Apparently, this was well within the norm of their usual fees for the inventory management system in place.

Granted, just being cheaper is usually not a good place to be in the market. Yet, when a competitor’s software is designed in such a way that it takes a small army of consultants to get it up and running, they can’t just lower their license fees to match yours – assuming that your design is not half-baked too. The competition would have to redesign their solution from scratch, and give up on their consultingware revenues. So you are in a great position to drive competition crazy.

With a market managing over two-thirds of the US gross domestic product, one would expected retail be saturated by fantastic software products. It turns out this is not the case. Not by a long shot – except eCommerce (e.g. online shopping carts) which attracts a zillion developers for no good reason.

Some salient aspects of the retail software market:

- Most retailers are already equipped in basic stuff such as point-of-sale, inventory management and order management systems. So you don’t have to deliver that yourself. On the contrary, you should rely on the assumption that such software is already in place.

- As far the Lokad experience goes with its online sales forecasting service, retailers are not unwilling to disclose their data to a 3rd party over the Internet. It takes trust and trust takes time. Interestingly enough, at Lokad we do sign NDAs, but rather infrequently. We are not unwilling, but most retailers (even top 100 worldwide ones) simply don’t even bother.

- Retailers have a LOT of data, and yet unlike banks, they have little talented manpower to deal with it. Many retail businesses are highly profitable though and could afford to pay for this kind of manpower, but as far I can tell, it’s just not part of the usual Western retail culture. Talents go to management, not to the trenches.

Niche 1: EOQ (Economic Order Quantity) calculator

Retailers know they need to keep their stocks as low as possible, while preserving their service levels (aka rate of non stock-outs), see this safety stock tutorial for more details. If the marginal ordering cost for replenishment was zero, then retailers would produce myriads of incremental replenishment orders, precisely matching their own sales. This is not the case. One century ago, F. W. Harris introduced the economic order quantity (EOQ) which represents the optimal quantity to be ordered at once by the retailer, when friction factors such as the shipping cost are taken into account. Obviously, the Wilson Formula (see Wikipedia for details) is an extremely early attempt at addressing the question. It’s not too hard to see that many factors are not accounted for, such as non-flat shipping costs, volume discounts, obsolescence risks …etc.

Picking the right quantity to order is obviously a fundamental question for each retailer performing an inventory replenishment operation. Yet, AFAIK, there is no satisfying solution available on the market. ERP systems just graciously let the retailer manually enter the EOQ along with other product settings. Naturally, this process is extremely tedious, firstly because of the sheer number of products, secondly because whenever a supply parameter is changing, the retailer has to go through all the relevant products all over again.

The EOQ calculator would typically come as multi-tenant web app. Main features being:

- Product and supplier data import from any remotely reachable SQL database[1].

- Web UI for entering / editing EOQ settings.

- EOQ calculation engine.

- Optional EOQ export back to the ERP.

Pricing guestimate: Charge by the number of products rather than by the number of users. I would suggest to start around $50/month for small shops and go up to $10k/month for large retail networks.

Gut feeling: EOQ seemingly involves a lot of expert knowledge (my take: acquiring this knowledge is a matter of months, not years). So there is an opportunity to position yourself as an expert here, which is a good place to be as it facilitates inbound marketing and PR with specialized press. Also, EOQ can be narrowed down to sub-verticals in retail (e.g. textiles) in case competition grows stronger.

Niche 2: Supplier scorecard manager

For a retailer, there are about 3 qualities that define a good supplier: lowest prices, shortest shipment delays, best availability levels (aka no items out-of-stock delaying the shipments). Better, sometime exclusive, suppliers give a strong competitive edge to a retailer. Setting aside payment terms and complicated discounts, comparing supplier prices is simple, yet, this is only the tip of the iceberg. If the cheapest supplier doesn’t deliver half of the time, “savings” will turn into very expensive lost sales. As far I can observe, beyond pricing, assessing quality of the suppliers is hard, and most retailers suffer an ongoing struggle with this issue.

An idea that frequently comes to the mind of retailers is to establish contracts with suppliers that involve financial penalties if delays or availability levels are not enforced. In practice, the idea is often impractical. Firstly, you need to be Walmart-strong to inflict any punitive damage on your suppliers without simply losing them. Secondly, shipping delays and availabilities needs to be accurately monitored, which is typically not the case.

A much better alternative, yet infrequently implemented outside the large retail networks, consists of establishing a supplier scorecard based on the precise measuring of both lead times (i.e. the duration between the initial order and the final delivery) and of the item availability. The scorecard is a synthetic, typically 1-page, document refreshed every week or every month that provides the overall performance of each supplier. The scorecard includes a synthetic score like A (10% best performing suppliers), B and C (10% worst performing suppliers). Scorecards are shared with the suppliers themselves.

Instead of punishing bad suppliers, the scorecard helps them in realizing there is a problem in the first place. Then, if the situation doesn’t improve after a couple of months, it helps the retailer itself to realize the need for switching to another supplier…

The scorecard manager web app would feature:

- Import of both purchase orders and delivery receipts (this might be 2 distinct systems). [2]

- Consolidation of per-supplier lead time and availability statistics.

- One-page scorecard reports with 3rd party access offered to the suppliers.

Pricing guestimate: Charge based on the number of suppliers and the numbers of orders to be processed. Again, the number of users having access to the system might not be a reliable indicator. Starting at $50/month for small shops up to $10k/month for large retail networks.

Gut feeling: By positioning your company as intermediate between retailers and their suppliers, you benefit from a built-in viral marketing effect, which is rather unusual in B2B. On the other hand, there isn’t that much expert knowledge (real or assumed) in the software itself.

Niche 3: Dead simple sales analytics

Retail is a fast-paced business, and a retailer needs to keep a really close eye on its sales figures in order to stay clear of bankruptcy. Globally, the software market is swarming with hundreds of sales analytics tools, most of them being distant competitors of Business Objects acquired by SAP years ago. However, the business model of most retailers is extremely simple and straightforward, making all those Business Intelligence tools vast overkill for small and medium retail networks.

Concepts that matter in retail are: sales per product, product categories and points of sale. That’s about it. Hence, all it should take to have a powerful sales visualization tool setup for a retailer should be access to the 2 or 3 SQL tables of the ERP defining products and transactions; and the rest being hard-coded defaults.

Google Analytics would be an inspiring model. Indeed, Google does not offer to webmasters any flexibility whatsoever in the way the web traffic is reported; but in exchange, setting-up Google Analytics requires no more than merely cutting-and-pasting a block of JavaScript into your web page footer.

Naturally it would be a web app, with the main features being:

- Product and sales data import from any remotely reachable SQL database.[2]

- Aggregate sales per day/week/month.

- Aggregate per product/product category/point-of-sales.

- A Web UI ala Google Analytics, with a single time-series graph per page.

Pricing guestimate: Regular per-usage fee, a la Salesforce.com. Starting at $5/user/month basic features to $100/user/month for more fancy stuff.

Gut feeling: probably the weakest of the 3 niches, precisely because it has too much potential and is therefore doomed to attract significant attention later on. Also, achieving a wow effect on first contact with the product will probably be critical to turn prospects into clients.

Market entry points

Worldwide, there are plenty of competitors already for these niches. Yet, again, this does not mean much. Firstly because retail is so huge, secondly because it’s a heavily fragmented market anyway. First, there are big guys like SAP, JDA or RedPrairie, typically way too expensive for anything but large retail networks. Second, there are hundreds of mid-market ERPs, typically with a strong national (or even regional) focus. However, those ERPs don’t delve into fine-grained specifics of retail, as they are too busy already dealing with a myriad of feature requests for their +20 modules (accounting, billing, HR, payments, shipping … etc). Hence, there is a lot of space for razor-sharp web apps that focus on one, and only one, aspect of the retail business. Basically single-minded, uncompromising obsession with one thing, leaving aside all other stuff to either ERPs or other web apps.

In order to enter the market, the good news is that mid-size retailers are pretty much everywhere. So you can just use a tiny bit of networking to get in touch with a couple of neighbouring businesses, even if you don’t have that much of a network in the first place. Then, being razor-sharp in a market where very little online content is available, offers you a cheap opportunity at doing some basic SEO based on the very specific questions your software is addressing.

Q: I am interested, I have questions, can I ask you those questions?

A: Naturally, my rate is 200€/h (no just kidding). Yes, email me.

[1] Don’t even bother about providing a super-complicated setup wizard. Just offer a $2k to $5k setup package that includes the ad-hoc handful of SQL lines to match the existing data of the retailer. We are already using this approach at Lokad with Salescast. Alternatively, we also offer an intermediate SQL schema, if the retailer is willing to deal with the data formatting on its own.

[2] Again, I suggest an approach similar to the one of Salescast by Lokad: don’t even try to robotize data import, just design the software in such a way that adding a custom adapter is cheap.

Joannes Vermorel is the founder of Lokad, company motto “You send data, we return forecasts”. Lokad won the first Windows Azure award from Microsoft in 2010, out of 3000 companies applying worldwide. He has a personal blog that mostly deals with cloud computing matters.

Software developers seem to be herd animals. They like to stay very close to each other. As a result, the marketplace ends up riddled with

Software developers seem to be herd animals. They like to stay very close to each other. As a result, the marketplace ends up riddled with  On the 26th May the rules on the use of cookies changed for UK businesses. You now have to explicitly ask every visitor to your website if they want to opt-in to ‘non-essential’ cookies. This includes tracking and analytics cookies. The penalty for not doing so is a fine of up to £500,000.

On the 26th May the rules on the use of cookies changed for UK businesses. You now have to explicitly ask every visitor to your website if they want to opt-in to ‘non-essential’ cookies. This includes tracking and analytics cookies. The penalty for not doing so is a fine of up to £500,000. Choosing the right product to develop is crucial. Great execution is also very important. But if you develop a product that no-one wants or no-one is prepared to pay for, then you are going to fail, no matter how well you execute it. You can often tweak a product or its marketing to make it more successful based on market feedback (‘pivot’) . But the less pivoting you have to do, the better. Below I list some of the criteria I think are important for evaluating the potential of new commercial software products.

Choosing the right product to develop is crucial. Great execution is also very important. But if you develop a product that no-one wants or no-one is prepared to pay for, then you are going to fail, no matter how well you execute it. You can often tweak a product or its marketing to make it more successful based on market feedback (‘pivot’) . But the less pivoting you have to do, the better. Below I list some of the criteria I think are important for evaluating the potential of new commercial software products. Al Harberg (best known for his

Al Harberg (best known for his

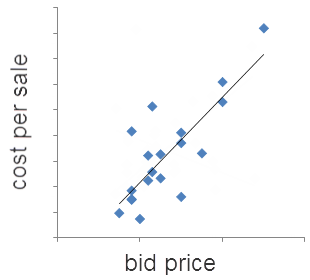

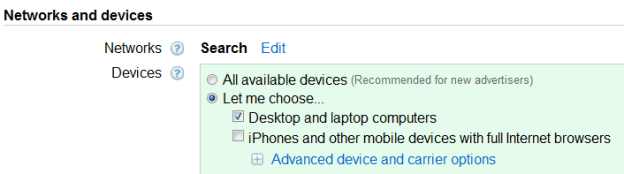

The results from analytics: 60% of the people clicking on the ads were on Windows and 40% on Mac.

The results from analytics: 60% of the people clicking on the ads were on Windows and 40% on Mac. The results from analytics: 73% of the people clicking on the ads were on Windows and 27% on Mac.

The results from analytics: 73% of the people clicking on the ads were on Windows and 27% on Mac. It is the Royal Wedding tomorrow and everything has gone Royal Wedding crazy here in the UK. I did send the happy couple a complimentary copy of my

It is the Royal Wedding tomorrow and everything has gone Royal Wedding crazy here in the UK. I did send the happy couple a complimentary copy of my  Through an unforeseen series of events, I have ended up corresponding with a cracker known only to me by a Hotmail address and the pseudonym “CrackZ”. It quickly became clear that he knew what he was talking about, but was motivated by curiosity rather than criminality. Obviously crackers are a more diverse group than the criminal masterminds and script kiddies of popular imagination. To my surprise he agreed to be interviewed for this blog and I jumped at the chance to find out a bit more about the shadowy world of cracking.

Through an unforeseen series of events, I have ended up corresponding with a cracker known only to me by a Hotmail address and the pseudonym “CrackZ”. It quickly became clear that he knew what he was talking about, but was motivated by curiosity rather than criminality. Obviously crackers are a more diverse group than the criminal masterminds and script kiddies of popular imagination. To my surprise he agreed to be interviewed for this blog and I jumped at the chance to find out a bit more about the shadowy world of cracking.